PART SIX

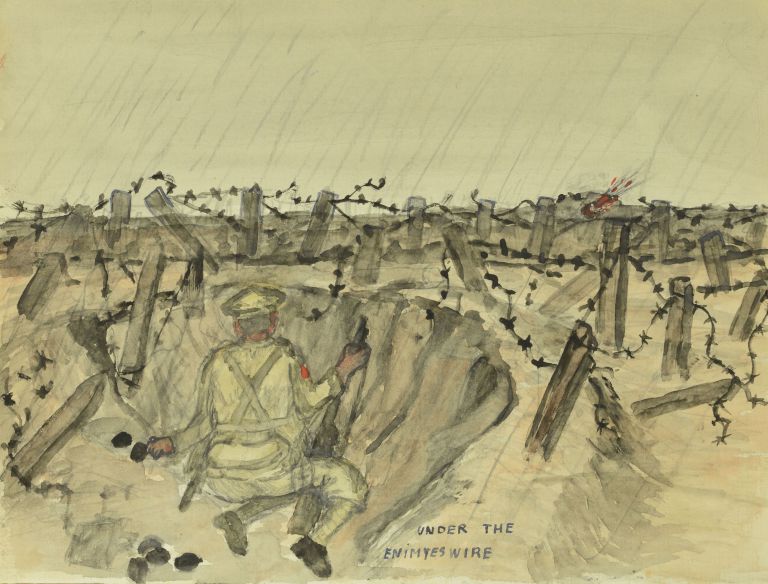

In the following extract abridged from Albert Clayton’s recently discovered WW1 memoir Long Before Daybreak Clayton lies wounded and alone in no man’s land. He remained there for three days.

The long, golden afternoon drew to a close; the purple dusk rose like a mist from the ground and I prepared to crawl out of my hole as soon as the afterglow had departed from the western sky.

It was only with great difficulty that I did eventually climb out, for every time my left foot came into contact with the ground the bones of my knee seemed to grind together, and red-hot needles shot up and down my leg. I flopped over into the next shell-hole in perspiring agony and rested a moment.

I was just gathering my strength, when a metallic sound cut the night. The sound of a pick and spade clanking together, to be followed later by the dull thud of many feet striking the earth with a shuffling beat. I crouched low in my hole in the darkness, waiting expectantly with one eye cocked open in the direction of the sound.

Then they appeared. A straggling file of Jerries in their ugly square-headed helmets. Obviously a working-party on their way up to the front line.

They had all passed safely by, I thought, when one, carrying a rifle, wandered rather nearer to my hole than the others had done and apparently caught sight of me. He was a nasty, mean looking, oldish sort of customer, wearing that most unmilitary appendage, a beard.

He stopped. I felt his evil stare bore into my back. Heard him mutter a string of guttural sounds which could have been nothing but curses. Then he stooped and picked up my rifle. He examined it carefully, trying the bolt like some gorilla investigating some strange object.

The picture I presented must have been ghastly to look upon. My tunic was torn and caked with dirt. My trousers all ripped and smeared with blood, revealed a blood-stained bandage wrapped loosely round a leg shining cadaverously white in the moonlight. I allowed my jaw to hang open as if in death, and put all my trust in the corpse-like effect I hoped to create.

Then the ugly bearded monster raised my own rifle and bayonet in the air. He’s going to stick it in me, I thought in a flash. In the space of a split second I expected to feel the penetration of cold steel plunging into my vitals. But the poised bayonet never descended.

My ghastly tableau served its purpose. He flung the rifle and bayonet violently away into the night hurling guttural curses after it, then turned and strode after his vanishing working-party.

The distance those tramping men seemed to travel and the remoteness of the Very lights I could see soaring up from the front line, began to raise in my mind the suspicion that I could never do it.

Sleep or faintness must have overcome me again, for almost before I was aware of it the night had slipped away and the light of a new day found me in the self-same shell-hole as before with another long wait for darkness confronting me.

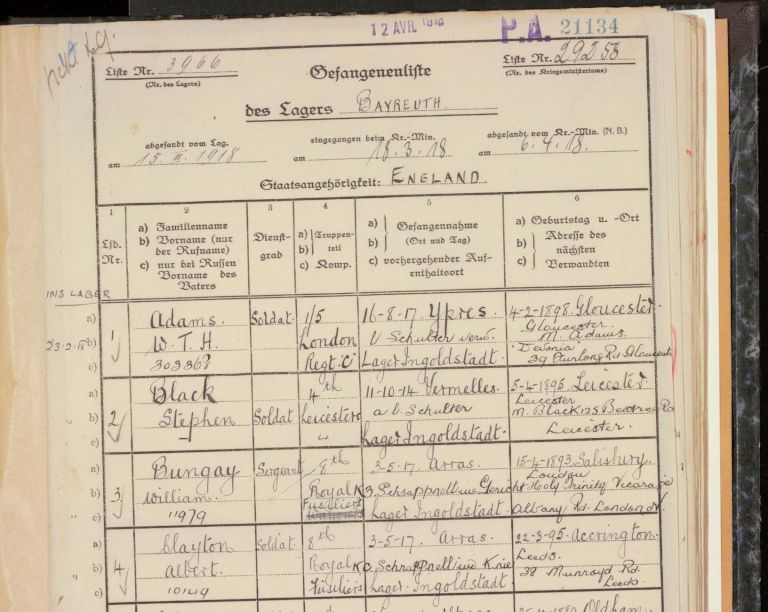

Clayton was captured by enemy forces towards the end of the Battle of Arras on 3rd May 1917.

He did not write about his experiences as a Prisoner of War, nor of his time in the POW hospital in Ingolstadt, Germany.

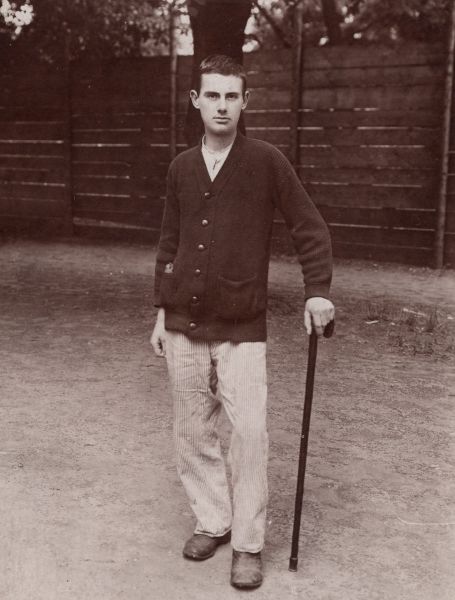

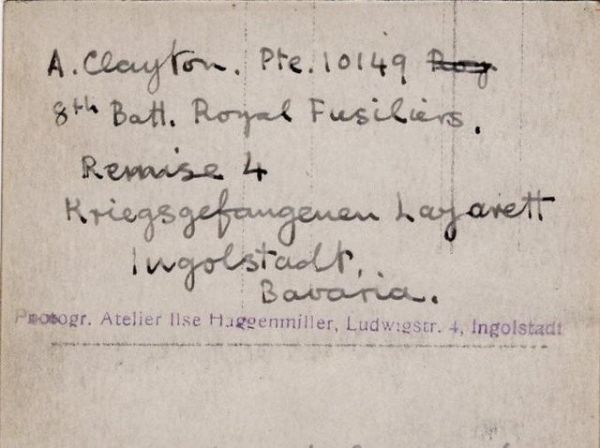

The two photographs found within his manuscript therefore offer a precious insight into this part of his war story.

This photograph was taken in August 1917, just a few months after Clayton was captured. We see him in the German Prisoner of War hospital in which he stayed until the end of the war. The reverse of the photograph (pictured) tells us that Clayton was housed in 'Remise [Outbuilding] 4'.

The final photograph shows a group of Prisoners of War, likely British and French soldiers. We do not know the names of the individuals nor who took the photograph. Perhaps it was Clayton himself, as he is not present in the photo, who took it, to remember his comrades during a difficult time in their lives.

After the war, Albert worked as an art teacher and died in 1981 aged 95. His wife Greta, also a trained artist, passed away eight years later.

We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to Micah Duckworth (pictured) for graciously allowing us to tell some of Clayton's incredible story. His memoir Long Before Daybreak, is available to purchase here.