PART ONE

The following extract abridged from Albert Clayton’s recently discovered WW1 memoir Long Before Daybreak describes his journey with the Royal Fusiliers battalion from their encampment on the French coast to the front line.

The summer of 1916 was a scorcher. From dawn till dusk the sun blazed down out of a cloudless, steel-blue sky, while the sweltering camp of Étaples shimmered in a haze of tropical heat and dust, raising many regrets for the cool and lovely city of Edinburgh we had recently left behind.

There were about three or four hundred of us who had been suddenly warned a few days before that we were due for France at any moment, had visited the barber for the usual prison crop given to soldiers on draft, and when the momentous departure order came, had been rushed practically non-stop by train and boat to Étaples.

I, Private Clayton, A. Number P.S.10149, of the 29th Royal Fusiliers, a so-called Public Schools Battalion, found myself numbered with that perspiring draft. Though actually more “Public” than “Public School”, the battalion did, however, contain a large percentage of students of one sort and another. Students from the newer universities, from technical colleges, business colleges, even theological colleges, plus a very strong quota of clerks from banks and city offices.

As for the art school life I had left behind, all this had vanished, leaving nothing but a heavy pack, a cumbersome gun, and the expectation of an early and painful death.

To the amateur soldier, one of the most disconcerting aspects of life in the rank and file, as well as one of the most aggravating, was the suddenness with which things happened. Orders simply fell out of the blue. One might just take a casual stroll into the nearest village to buy a packet of cigarettes and return as casually to find the whole company packed up and gone, disappearing down the road in a cloud of dust.

Indeed, it was in just this abrupt fashion that we finally left Étaples after a stay of about five days, heralded only by a ginger-headed corporal who stuck his head in through the tent flap early one morning and crudely broke the news.

“Parade in fifteen minutes, full marching order,” he yelled, “we’re moving off!”

“Where to?” demanded one optimist innocently, thinking they would tell him.

“Berlin,” came the answer, “where the ‘ell d’you think you’re going?”

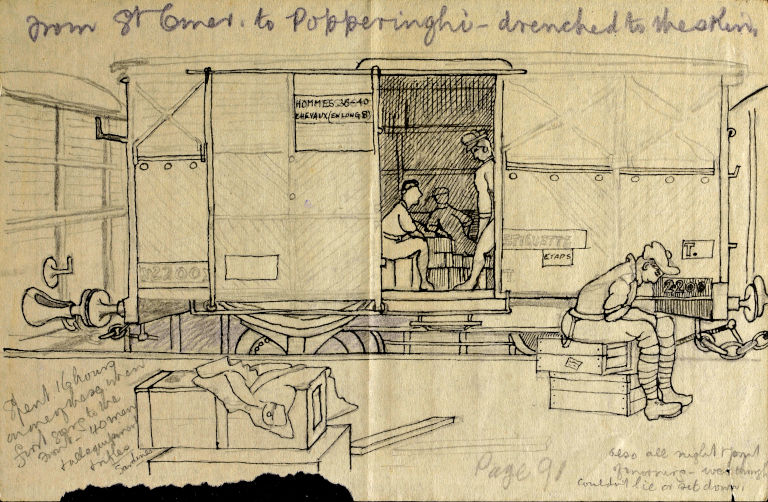

So within half an hour they had marched us down to the railway siding, our kit and equipment hanging on our backs; pack, gas-mask, rifle, ‘tin’ hat and all the rest of the oddments that bow down the heads and fray the tempers of the indomitable P.B.I. (Poor Bloody Infantry); to be packed into what somebody described with unintentional truth as “lousy cattle-trucks”.

The cattle-trucks, marked on the outside, “8 CHEVAUX 40 HOMMES,” were dark and dirty vans, without windows, the only entrance for light and air being by way of the open door. The wooden floor of my particular van suffered from a charred depression in the centre, where some destructive individual, careless of railway property, had once lit a fire to make a can of tea. Evidently the water boils before the fire burns through the bottom of the van.

And so, with many a weary halt and many a false alarm the train jogged slowly along, taking us nearer and yet nearer to nobody knew quite what, though everyone knew in his bones it was bound to be something unpleasant. Exactly what form this unpleasantness would take or how long before it would be thrust upon us, was a question that could only be answered by people of greater experience in such matters. For all we in our ignorance could tell, they might run these trains right up to the firing line itself (under cover of darkness, of course) and we might be expected to climb out of those doors under a whistling hail of bullets. Yes, even stranger things than that had happened... impossible as it seemed.

Certainly, a most ominous rumble in that rapidly approaching distance seemed to be getting louder and louder with every mile we travelled; like an impending thunderstorm, or the rumblings of exceptionally heavy traffic.

However, the train came to a final halt at last with one of those tremendous jerks that are so typical of the vivacious touch of French engine-drivers, and the call passed along the train, “ALL OUT!”

However, the train came to a final halt at last with one of those tremendous jerks that are so typical of the vivacious touch of French engine-drivers, and the call passed along the train, “ALL OUT!”

So throwing packs and equipment before us, we scrambled out into the glaring sunshine.

Long Before Daybreak by Albert Clayton is published in paperback and eBook on Amazon.

Further information at www.longbeforedaybreak.com